In the summer of 2011 a rural Illinois man named Wayne Sabaj was in his backyard picking broccoli. As he bent down, something caught his eye. Half buried in the dirt, he found a sealed nylon bag. Inside was $150,000 in cash. For Sabaj, who was unemployed and had, in his words, “spent my last ten dollars on cigarettes,” this was a godsend. Though it remains a mystery who had buried this particular stash of money, these sorts of finds are not uncommon. With some regularly, homeowners doing renovations unearth money buried in backyards, basements and bedroom walls. Oftentimes, these date to the Depression era, when there was greater concern about the solvency of banks, but not always. I personally have seen cash hidden away in some unusual places around homes.

While these stories are humorous, I would argue that people who squirrel away cash like this are not altogether irrational. In fact, I would go a step further and say that — as long as they don’t forget about it — these folks are actually making the right decisions with their money.

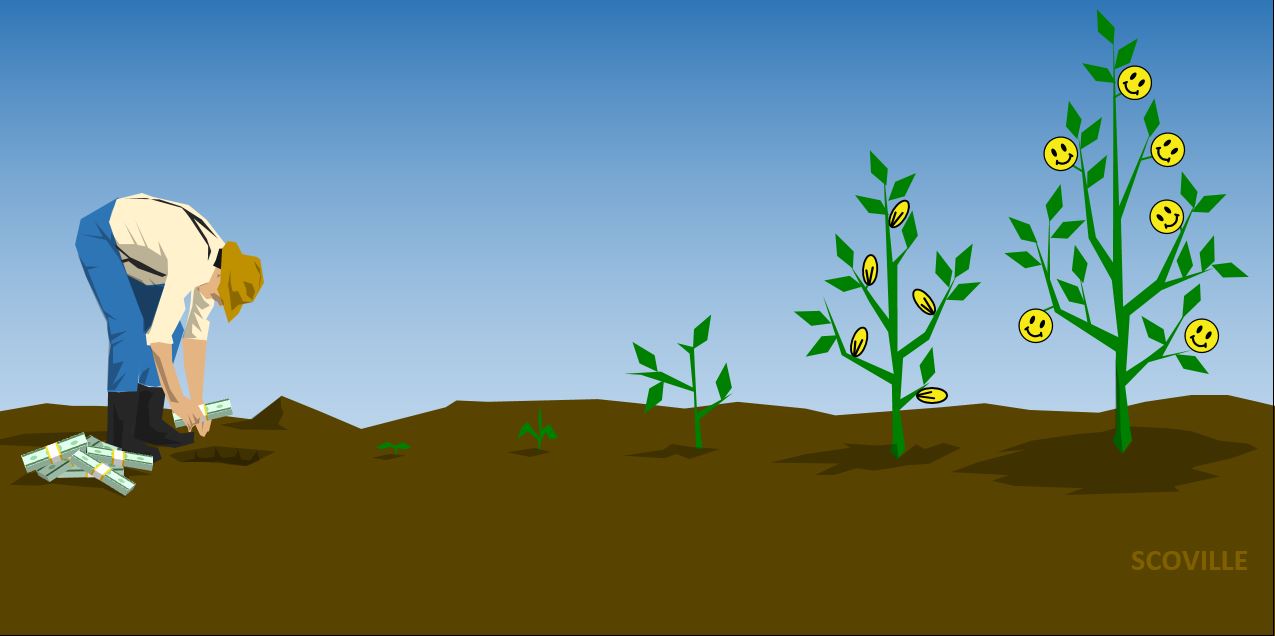

Why? The reality is that many, if not most, of our financial decisions are driven by emotional goals and not by any kind of logical or numerical cost-benefit analysis. While perhaps less colorful than hiding money in the broccoli garden, we all make financial decisions that are motivated by what makes us feel good. Whether it is a five-dollar latte or a thousand-dollar phone or a hundred-thousand-dollar sports car, we all allocate money in ways that bring us happiness, even if they might seem irrational to the next person.

In my view, a cash hoard is no different. Whether it is in the garden or in the bank, if this is what provides you with happiness and security, then I would say this is, by definition, the right way to allocate your resources.

And it’s not just cash. People often struggle with financial decisions when the “right” answer from a numerical standpoint doesn’t feel like the right answer from an emotional standpoint. Consider these examples:

Suppose you live in New York City, where the cost of living is 50 or 100 percent higher than it might be somewhere else. Yes, you could move and keep more money in your pocket, but you’d also be giving up a lot in terms of quality of life, so you stay.

Suppose you have a very low-rate, 30-year mortgage. The math would say that you shouldn’t pay down this mortgage any faster than you need to, even if you have the financial wherewithal to do so. But, emotionally, you like the feeling of being debt-free, so you pay it off.

Suppose your grandmother left you a handful of shares in a collection of companies that you don’t completely understand. Sure, you could sell them and diversify the proceeds, but each time you open your monthly statement, the shares remind you of your grandmother, so you decide to keep them.

I wouldn’t criticize any of these choices. Just because they seem like purely financial decisions doesn’t mean that they need to be decided on a purely quantitative basis. I don’t see them as being any different from the choices I mentioned earlier — to drive a fancy car, for example. All of these choices are, in fact, rational decisions in the sense that they bring the individual happiness or security. For that reason, you shouldn’t worry if you want to make a decision in this way.

I will add just one caveat: Decisions like this are all okay as long as they are in the context of an overall financial plan that is designed to get you where you want to go. I definitely would be concerned and would recommend a change if your excessive cash holdings or your sentimental attachment to a stock or your decision to live in a high-cost city were jeopardizing your retirement. But, if a certain financial choice will bring you happiness, and it won’t hurt you, then I wouldn’t be concerned, and I wouldn’t be concerned what your friends or your family or your neighbors think.

At the end of the day, your financial assets should bring you happiness and peace of mind. If that means burying it in the backyard, that’s perfectly okay. Just don’t forget where you put it.